How do you prove who you are to a computer?

You could just use a password, a shared secret between you and the machine. But passwords are easily compromised—through a phishing scam, or a data breach, or some good old-fashioned social engineering—making it simple to impersonate you.

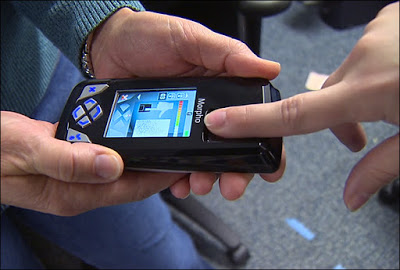

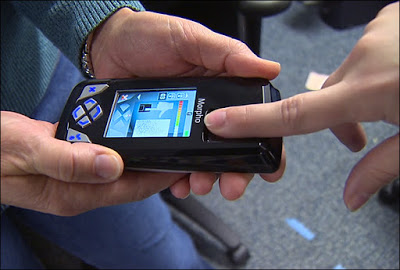

Today, you’re often asked to produce something more fundamental and harder to imitate than a password: something that you are rather than something that you know. Your fingerprint, for instance, can get you into a smartphone, a laptop, and a bank account. Like other biometric data, your fingerprints are unique to you, so when the ridges of your thumb come in contact with a reader, the computer knows you’re the one trying to get in.

Your thumb is less likely to wander off than a password, but that doesn’t mean it’s a foolproof marker of your identity. In 2014, hackers working for the Chinese government broke into computer systems at the Office of Personnel Management and made off with sensitive personal data about more than 22 million Americans—data that included the fingerprints of 5.6 million people.

That data doesn’t appear to have surfaced on the black market yet, but if it’s ever sold or leaked, it could easily be used against the victims. Last year, a pair of researchers at Michigan State University used an inkjet printer and special paper to convert high-quality fingerprint scans into fake, 3-D fingerprints that fooled smartphone fingerprint readers—all with equipment that cost less than $500.

The fundamental trouble with biometrics is that they can’t be reset.

In the absence of a state-sponsored cyberattack, there are other ways to glean someone’s fingerprint. Researchers at Tokyo’s National Institute of Informatics were able to reconstruct a fingerprint based off of a photo of a person flashing a peace sign taken from nine feet away. “Once you share them on social media, then they’re gone,” Isao Echizen told the Financial Times.

Face-shape data is susceptible to hacking, too. A study at Georgetown University found that images of a full 50 percent of Americans are in at least one police facial-recognition database, whether it’s their drivers’ license photo or a mugshot. But a hacker wouldn’t necessarily need to break into one of those databases to harvest pictures of faces—photos can be downloaded from Facebook or Google Images, or even captured on the street.

And that data can be weaponized, just like a fingerprint: Last year, researchers from the University of North Carolina built a 3D model of a person’s head using his Facebook photos, creating a moving, lifelike animation that was convincing enough to trick four of five facial-recognition tools they tested.