Heineken suddenly transferred the Managing Director of Nigerian Breweries, Nico Vervelde, to Singapore shortly after Nigerian police interrogated him for alleged corruption.

This case would have been buried if journalists Olivier van Beemen and Femke van Zeijl had not picked it up. They recently won De Tegel, the most prestigious award for journalism in the Netherlands, for their revelations about high-end corruption at Nigerian Breweries, a subsidiary of the multinational Heineken. Now PREMIUM TIMES presents their award-winning story for the first time to a Nigerian audience.

I – Nigeria, the Promised Land

On February 6, 2017, Nico Vervelde gives an interview to the Dutch weekly Elsevier. The managing director (MD) of Heineken’s subsidiary, Nigerian Breweries (NB), does not get any critical questions. At the Radisson Blu in Ikeja, Lagos, he talks freely about his life as an expat (‘I love an international environment’), the phenomenal success of his company and his love for golf and jogging. He has been living in the country for seven years and has no plans to move. ‘I’m having a great time in Nigeria.’

Less than three months later, Mr Vervelde suddenly resigns and is transferred to Singapore for a role that is yet to be specified. There is no successor yet. What went wrong?

Mr Vervelde is not just anyone. As the MD for Heineken in Nigeria, he’s considered to be one of the most successful managers of the world’s number two brewing company (after AB Inbev). Nigeria is in the top 3 of its most profitable markets in the world and by far the most important African country: it delivers about half of the brewer’s revenue continent-wide. At the international headquarters in Amsterdam (Netherlands), Nigeria is sometimes referred to as ‘the promised land.’

What the Elsevier story doesn’t say is that one month before the interview, Mr Vervelde was interrogated at the headquarters of the federal police in Abuja. The questions he had to answer there were considerably more challenging. The police wanted to know everything about a notorious corruption case in which his wife was the prime suspect and he a key witness. The case made headlines in Nigeria and internationally, but was never followed up.

To understand what has happened, we have to go back to a jet-set party in Lagos in 2013, attended by the oil trader, Amadu Sule. On that occasion, Mr Sule is introduced to Clémentine, a woman he describes as ‘not young but stunning’. She gives him a business card in the name of her company, Limitless Mind Africa, specialised in musical productions, conferences, artist management ‘and more.’

This is no exaggeration. Clémentine does more, much more. Consultancies, for instance, and managing a network of excellent connections. She has a nice proposition: Would Mr Sule consider becoming the oil supplier for Nigerian Breweries?

Coming from the Islamic north and remembering that his recently departed father had always forbidden him to do business with alcohol producers, he hesitates. But he is not that strict himself, and besides, it dawns on him that this is not a matter of a few barrels of diesel for some lorries.

Most of the breweries rely completely on generators that consume millions of litres every year. Of course, he’s interested!

But what about the public tender? As a listed company and part of a multinational with operations around the world, Nigerian Breweries has strict procedures for these kinds of contracts. Nothing to worry about, assures Clémentine. In exchange for a fee, she will arrange everything, starting with meeting the MD, Mr Vervelde. Mr Sule is impressed by her straightforwardness and has a good feeling. It is only when he arrives at his home and puts the two call cards next to each other that he notices they carry the same surname. But he considers it impolite to enquire further.

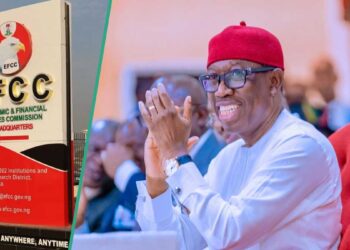

Nico Vervelde [Photo: Nigerian Breweries]

Shortly thereafter, Mr Sule is invited to the Vervelde home in upmarket Banana Island. Here, he also meets Jasper Hamaker, the finance director at Nigerian Breweries. Sule: “He saw opportunities for me,” Mr Sule says. And indeed there were. In the autumn of 2013, TMDK Oil Traders, Mr Sule’s company, became the oil supplier for the Kaduna and Ama breweries. The latter is Heineken’s largest brewery on the continent, located near the city of Enugu. The contract is valid for three years and Mr Sule claims he makes an oral agreement with Clémentine for another two years. Nigerian Breweries is expected to buy 3 million litres per month, making the entire deal worth some $60 million. They agree on a first payment: $200,000 in cash. “I paid and she chucked out the previous supplier,” the businessman recalls.

But the honeymoon does not last. Irritation arises when Mr Sule is accused of delivering sub-standard oil, supposedly causing a fire in the Ama brewery. An internal inquiry concludes there is nothing wrong with his product and rumours circulate that the fire may well have been the result of arson, an attempt to tarnish Mr Sule’s name. And then there is a drastic reduction in the monthly orders, as the breweries makes a partial change from oil to gas, another setback for Mr Sule. The oil trader says that this is in breach of his deal he had made with Clémentine. Meanwhile, she keeps asking for more money.

And she’s not the only one. “Everybody has to be bought off,” Mr Sule says, “also at the lower levels.”

A Dutch former internal source confirms that suppliers routinely have to pay bribes. “A guard charges you N100 to let you in. At a slightly higher level, you pay N1,000 and once you’re at the level of the financial controller, you easily need a couple of million naira if you want to get paid. That’s how it works.”

Mr Sule is fed up. His people, the Fulani, are known to be proud and headstrong, and he comes from an influential family: they are messing with the wrong guy. When the controller and a colleague demand another $20,000, he pays. But this time he does it through the bank, with proof of payment. He then confronts the top management of Nigerian Breweries and the auditing department. The company is forced to react: both employees are fired and an internal inquiry gets underway, leading to more dismissals. Amsterdam Head Office is also informed and starts its own investigation.