President Trump has egged on a new arms race. Russia violated weapons

treaties to upgrade its nuclear arsenal. North Korea is developing

long-range missiles and practising for nuclear war — and the US military

is considering preemptive attacks on the isolated nation’s military

facilities.

Meanwhile, nuclear terrorism and dirty bombs remain a sobering threat.

Though these events are unlikely to trigger the last-ditch option of

nuclear war, let alone a blast in your neighbourhood, they are very

concerning.

So you might be wondering, “If I survive a nuclear-bomb attack, what should I do?”

Michael Dillon, a Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory researcher,

crunched the numbers and helped figure out just that in a 2014 study

published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A:

Mathematical and Physical Sciences.

Likewise, government agencies and other organisations have also

explored the harrowing question and came up with detailed

recommendations and response plans.

The scenario

You are in a large city that has just been subjected to a single, low-yield nuclear detonation, between 0.1 and 10 kilotons.

This is much less powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima — about

15 kilotons. However, it’s not unlikely when looking at weapons like

the new B61-12 gravity bomb, which is built by the US, maxes out at 50

kilotons, and can be dialed down to 0.3 kilotons. (Russia and Pakistan

are working on similar so-called “tactical” nuclear weapons.)

Studies have shown that you and up to 100,000 of your fellow citizens

can be saved — that is, if you keep your wits about and radiation

exposure low enough.

One of your biggest and most immediate goals is to avoid nuclear fallout.

How to avoid fallout radiation

Fallout is a mess of bomb material, soil, and debris that is

vaporised, made radioactive, and sprinkled as dust and ash across the

landscape by prevailing winds. (In New York City, for example, a fallout

zone would spread eastward.)

The best thing to do is to find a good place to hide — the more dense

material between you and the outside world, the better — then wait

until the rescuers can make their way to help you.

The US government recommends hiding in a nearby building, but not all of them provide much shelter from nuclear fallout.

Poor shelters, which include about 20% of houses, are constructed of

lightweight materials and lack basements. The best shelters are thick

brick or concrete and lack windows. Like a bomb shelter.

Hiding in the sub-basement of a brick five-story apartment building,

for example, should expose you to just 1/200 of the amount of fallout

radiation outside.

Meanwhile, hanging out in the living room of your one-story,

wood-frame house will only cut down the radiation by half, which — if

you are next to a nuclear explosion — will not do much to help you.

So, what do you do if there isn’t a good shelter right near you?

Should you stay in a “poor” shelter, or risk exposure to find a better

one? And how long should you wait?

Should you stay or should you go?

In his 2014 study, Dillon developed models to determine your best

options. While the answer depends on how far away you are from the

blast, since that will determine when the fallout arrives, there are

some general rules to follow.

If you are immediately next to or in a solid shelter when the bomb

goes off, stay there until the rescuers come to evacuate you to less

radioactive vistas.

If you aren’t already in a bomb shelter, but know a good shelter is

about five minutes away — maybe a large apartment building with a

basement that you can see a few blocks away — his calculations suggest

hoofing it over there quickly and staying in place.

But if the nice, thick-walled building would take about 15 minutes

travel time, it’s better to hole up in the flimsy shelter for awhile —

but you should probably leave for a better shelter after roughly an hour

(and maybe pick up some beers and sodas on the way: A study in the ’50s

found they taste fine after a blast).

This is because some of the most intense fallout radiation has subsided by then, though you still want to reduce your exposure.

Other fallout advice

One of the big advantages of the approach that this paper uses is

that, to decide on a strategy, evacuation officials need to consider

only the radiation levels near shelters and along evacuation routes —

the overall pattern of the radioactive death-cloud does not factor into

the models. This means decisions can be made quickly and without much

communication or central organisation (which may be spare in the minutes

and hours after a blast).

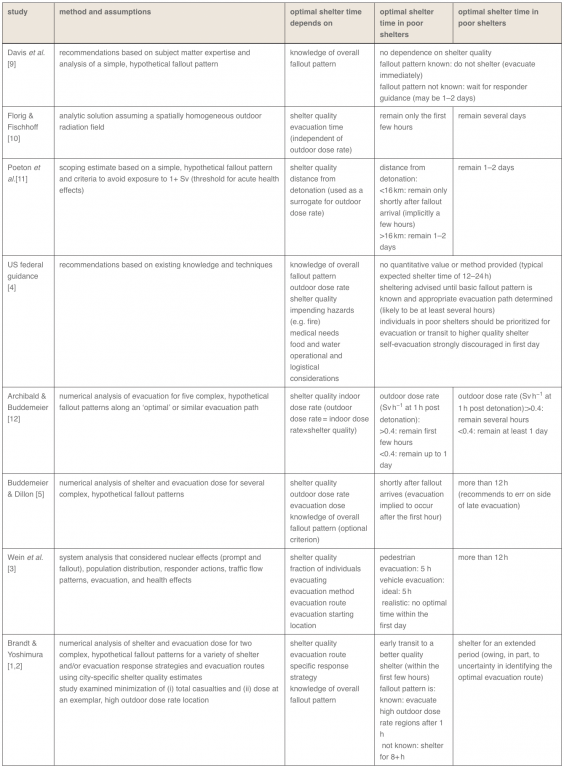

Other researchers have analysed other similar scenarios in papers, whose findings are summarised in the chart below: