What is the motivation behind the project to repatriate classic African art pieces?

I think it’s first useful to understand the context—how all of this first started. As a child growing up in Paris, I was always surrounded by classic African art. Even though I wasn’t consciously aware about African art, my parents taught me the importance of cultural identity, and how art was a vital part of that identity. My father had developed a taste for classic African art and I grew up with these pieces in our home. He was also friends with the collector, Jean Cambier. Aged 12, I made weekly visits to Jean’s home to see his collection. Much like a museum, his home was built around his art. We’d taste wine together and sat on medieval chairs, we’d both view his latest classic African art acquisitions—it was like a ceremony, like an initiation. Those weekly visits planted a seed in me, they made me discover the ‘powerful art of exorcism’.

My family left Paris for the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) in 1994, after which I left for Angola in 2000. Angola and DR Congo share common cultures and people, and even though Luanda is only a 45 minute flight away from Kinshasa, I was surprised by how little I knew about the Angolan reality, the nation, its people, and its cultures. But they certainly moved me. The environment in Angola at the end of the war was galvanic. Angola knew who she was, her people didn’t care about perceptions—they are loud and proud. Angolans have control over their narrative, they are true to themselves and demand respect. The end of the war in Angola was also a special moment in history, when Angolans felt that nothing could defeat them.

The other event that I remember having an impact on me was a visit I made to Paris. My family was looking to buy an apartment there. We viewed a very beautiful apartment that belonged to a music producer and his wife. The ground floor of the apartment had César sculptures on display, and walking up the stairs, hung on the wall was the Jean-Michel Basquiat painting

‘Pharynxs’. I was floored. It was a right hook to my stomach. The conversation with the homeowner very quickly turned from the apartment to his art collection.

The question of bringing back classic African art is very recent, the project started in earnest in 2013. The thing I first realised when I was so impacted by the Basquiat painting, is how his powerful contemporary art found its roots in African heritage. I thought, wouldn’t it be great if today’s African artists can also be inspired by their heritage, by works created by their ancestors. Exposing today’s artists to classic African art could be an interesting key to unlocking the potential of new artistic themes. I wanted to be an engine, to grab as much of Angola’s energy as possible and spur on the next generation of artists.

You’re also a collector of classic African art. Why did you make the transition from collecting contemporary art to classic?

The thing I love about the African practice of art is that it’s not about the artist or aesthetic impression. It’s about a higher purpose. The ability to give shape to the invisible world, a spirit. That’s not only what make it different, but also makes it superior to other art practices.

I first started personally buying classic African art pieces at auctions—at Christie’s and Sotheby’s—where I’ve bought contemporary art in the past. I then became friends with dealers Tao Kerefoff and Didier Claes. Through them, I continued growing and curating my collection. I organised my collection by going for not only what I liked but also what I felt was the best in its class. I am working to have all the main streams of African classic art as well as the best possible quality of each object. Each piece I buy has to fulfil the historic and pedigree requirements—it’s been exhibited, has a strong provenance, and has been featured in important books and catalogues. I want masterpieces that belong in the pages of the best art books.

A lot has been written about African art but primarily from an ethnographic or anthropological point of view. Very little has been written about the art itself or about the artists that created the pieces. So I made it my mission to gather as much information about the art as I could. I sourced the best books and tried to learn all that I could about classic African art.

Collecting contemporary African art, and growing up around classic art has trained my eye and given me the taste and self-confidence to collect classic African art masterpieces. The objects in my collection have to be AAA.

“I’m working to create the best collection of classic African art in the world.”

What spurred you on to repatriate stolen works from the Dundo museum?

One book I found while trying to expand my knowledge about classic African art was by the art historian Marie-Louise Bastin—’La Sculpture Tshokwe’. Leafing through the pages, I saw pictures of objects of the Dundo museum in Angola. One picture struck me, it was a huge closet full of mwana pwo masks. I thought “wow, this is so cool. Who knew that such a small museum held masterpieces worth many millions of dollars!” I told Didier that we had to visit the museum and see the pieces in person.

We made an appointment with the museum’s director, rented a small jet, and made our way to the newly renovated but remote museum. The place was impeccable, the government had spent a sum of money rehabilitating the museum. It had an ethnographic feel to it—spears, wall paintings, thrones of chiefs, and everyday kitchen utensils were on display all to show how ancestors used to live. The museum also had a small library where everything was well documented. However what we didn’t see were the mwana pwomasks in the book. We didn’t see any treasures of Chokwe art. I asked the director if he had any of the masks from the MarieLouise Bastin book. He said that what they used to have had been looted during the war, sold into private hands, and that there was no way they could be found. This revolted me. First, how could the government have invested so much in a museum without understanding the value and relevance of the art itself? We were looking at our history with exotic eyes—’this is how the savages used to live’. And second, with a museum like Dundo, there is no excuse for masterpieces that belong to the museum to not be there.

Didier told me that when he was a kid in DR Congo, in the late ’80s, a number of pieces from the Dundo passed through Kinshasa. So based on that early memory, we formed a team— which included Tao, Agnes Lacaille (Africanist and museologist), a number of researchers, and lawyers—and we started looking for the looted pieces. We asked the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren for access to their archives concerning Angolan museums and began work to identify pieces that were once in the Dundo museum’s collection.

“It’s important to use numbers and valuation to trigger public interest and debate on the value of culture.”

I ensured that we followed a pragmatic approach. I’m a collector, I know how this market works, I know when a piece stinks, so I know that if I go after that piece I’m taking a risk. I understand that in collecting African classic art, there can be significant amounts of money involved but I also know that the market spun out of control about five years ago. I also know that many of the Chokwe pieces we were looking to return back to the Dundo museum were bought in the ’80s and ’90s. So I decided that I would personally buy back the pieces for the museum but that I would only pay the price the collector or dealer paid for it when it was first acquired. I would give them the money they spent on the piece but not a dollar more.

The discussion to repatriate works of art back to their origin isn’t new. Why is now different for African art?

Let’s use the Greek as an example. 99% of Greek heritage is well documented, studied and accessible to its people. Everyone in Greece has a clear conscience about the fact that theirs is the birthplace of modern Europe. They understand who they are, where they come from and what they are worth—their art contributes to this understanding.

These are fundamental things missing in parts of Africa today. We don’t have access to our heritage and we don’t understand how important that heritage is to our self-worth, confidence, knowledge, and understanding. Without that knowledge, it’s impossible for us to be valid and productive citizens with centres of our own thought. It’s impossible for us not to be puppets. We are missing roots and that’s why I feel it’s vital for us to reconnect with classic African art. To be proud of the treasures that have long been forgotten.

I was watching a documentary last week in which the presenter was talking about the history of the Congo River. In it, the presenter described how Diogo Cão, the Portuguese explorer, discovered the river and erected a huge stone pillar to signify the discovery. Stood by the stone, she said, “This is where our history begins”. I found it so interesting that even today, after all the struggles countries like DR Congo and Angola have faced to date, we still believe that our history starts the first day a white guy laid eyes on us. It says so much about the distance we still have to cover in order to be the centre of gravity of ourselves. We still have a lot of work to do to take control of our history. We will never reach the level of economic development we desire if we don’t know who we truly are.

Some may counter your efforts with this argument: “Should the Louvre return Italian art to Italy? That art was taken by force. Where does it stop?”

Democracy is sensitive to public opinion but it can’t take the heat when its morals and ethics are called into question.

Not only did Africa start the race late, we now unfortunately don’t know in which direction to run. However the important thing is that the debate has been triggered. People are generally sympathetic to the cause because it is clearly defined. This is a debate about self-affirmation, a fight to demand respect and dignity. For me, I feel I am doing my part for my kids and grandkids. I have a responsibility as a father to clarify the struggle and put my own finger on the heat. It’s no longer enough to be the ‘nice African’, that’s counter-productive. I believe that to be fully realised Africans, we have to first have a sense of self-worth and understand what we stand for. We have to understand that we belong to a chain, a trajectory that started way before us and will go way beyond us. Our worth doesn’t begin when someone lays eyes on us. This has to be addressed seriously and I choose to do it through art and culture.

The looting of classic African art is an ongoing problem. Do you worry repatriated works will again be stolen from the Dundo Museum?

This won’t happen at the Dundo. The work we’ve done has been to raise the self-consciousness of Angolans. The looted works were returned to Angola on the official day the fight for her independence started. The pieces were presented to the Chokwe king and to the president of the republic. Important members of government and of parliament were also in attendance. It was an important political statement that said, this is the return of our history and identity. This is the return of a part of us. When you make it official, and not just a detail, it triggers a sort of consciousness and self-awareness in people. Everyone comes together around an area that is like a sort of truce in the nation.

I strongly feel that because the pieces were returned in this political and cultural context, we won’t have looting problems in the future.

What have been some of your successes with the project?

Some objects we’ve found in private collections and others we’ve found with dealers. Everyone’s interested in sitting on something to watch its value grow, especially dealers. For example, there is an important statue of a Chokwe princess, now back at the Dundo, which a dealer owned. He didn’t want to sell it for less than 1 million USD. I paid him 70 thousand USD. Now that’s still a lot of money but we had to get it back to the museum at a fair price.

Another collector actually contacted us, unprompted, to give back a Chokwe chair that he believed was looted. He didn’t want any money for it, he just wanted to be introduced to the Chokwe king and to visit the museum. I will make a point of personally ensuring that that happens before the end of the year to much fanfare. It’s important to reward those that treat us like people and not like ‘black people’.

Right now, we’ve identified and located about 40 pieces all looted from the Dundo museum. We’re trying to stay focused. This isn’t a general question about all African treasures, that’s too broad. We have the law on our side with this cause—it’s illegal to own museum registered pieces. Of the 40 pieces identified, we have brought back five, some of which are really important art objects. We’ve so far found several mwana pwo masks out of the 30 in the photograph. That image is a constant reminder of what still needs to be achieved.

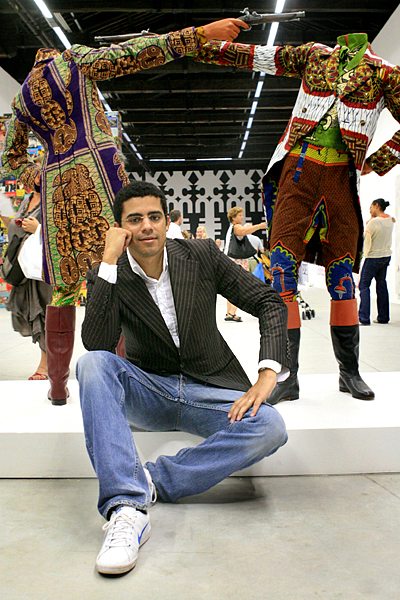

I’m working to create the best collection of classic African art in the world – Sindika Dokolo

0

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

BROWSE BY CATEGORIES

- #SmartLagos

- Basketball

- Beauty

- Boxing

- Breaking

- Business

- Careers

- Crime

- Default

- Education

- Entertainment

- Event

- Fashion

- Featured

- Football

- Gaming

- Gist

- Golf

- Health

- Inspirational Patience

- Interview

- Investigative

- Law

- Lifestyle

- local

- MetroMan

- MetroPerson

- metroplus

- MetroProfile

- Movies

- Music

- MUSIC

- New Music

- News

- nolly wood

- Nollywood

- Novels

- Odawood

- Opinion

- Parenting

- Photos

- Politics

- Press Release

- Relationship

- Religion

- Scandal

- Security

- Sex

- Society

- Sports

- Technology

- Travel

- TV

- Videos

- Weird

- Wheels

- World

BROWSE BY TOPICS

#COVID19Nigeria

#EndSARS

Adams Oshiomhole

Akinwunmi Ambode

APC

ASUU

atiku

Atiku Abubakar

boko haram

Buhari

Bukola Saraki

CBN

court

COVID-19

crime

davido

ECOWAS

Edo Election

Edo State Election

efcc

Featured

FG

Goodluck Jonathan

gunmen

INEC

Kayode Fayemi

Lagos

Lagos State

Muhammadu Buhari

NCDC

NDLEA

news

Niger

Nigeria

NLC

Obaseki

PDP

police

politics

President Buhari

Sanwo Olu

senate

tinubu

wike

Yemi Osinbajo

© Copyright MetroNews NG 2020. All rights reserved.